Victorian author and adoptee Brendan Watkins calls for a national inquiry into the hidden children of priests.

(Originally published in the VANISH VOICE August 2023 edition)

As most VANISH members would know, searching for one’s natural parents can be a long and difficult process, with unexpected revelations along the way. But when Brendan Watkins started his search 30 years ago, no one could have predicted what he would ultimately discover: his parents were a Catholic priest and nun.

Brendan arrives early for our interview at the VANISH office, a tall, striking figure dressed in Melbourne black. It’s two days after the release of his memoir Tell No One, which he celebrated with a book launch at a pub in Richmond, around the corner from where he grew up with his adoptive parents, Roy and Bet, and brother Damien. How does he feel now that the book is out? “I don’t know,” he says. “I feel as though my feet haven’t touched the ground since.”

Adopted in 1961, Brendan’s search was initially motivated by a desire to know his medical history, prompted by plans to start a family with his partner Kate, who had inherited a rare medical disorder. After applying to Community Services Victoria, he was directed to the Catholic Family Welfare Bureau, who, as Brendan has since learned, “saw itself as the protector of the mother from the child.” Brendan’s social worker, cold and foreboding, reluctantly contacted his mother on his behalf after Brendan’s insistence. Several weeks later, Brendan rushed back to her office, only to be told: “You’ll never see or talk to your mother. Go home, forget about it forever.” In a recent interview for ABC Compass, Brendan said: “It’s the most wounding, impactful trauma of my life. I’ve only just realised that.”

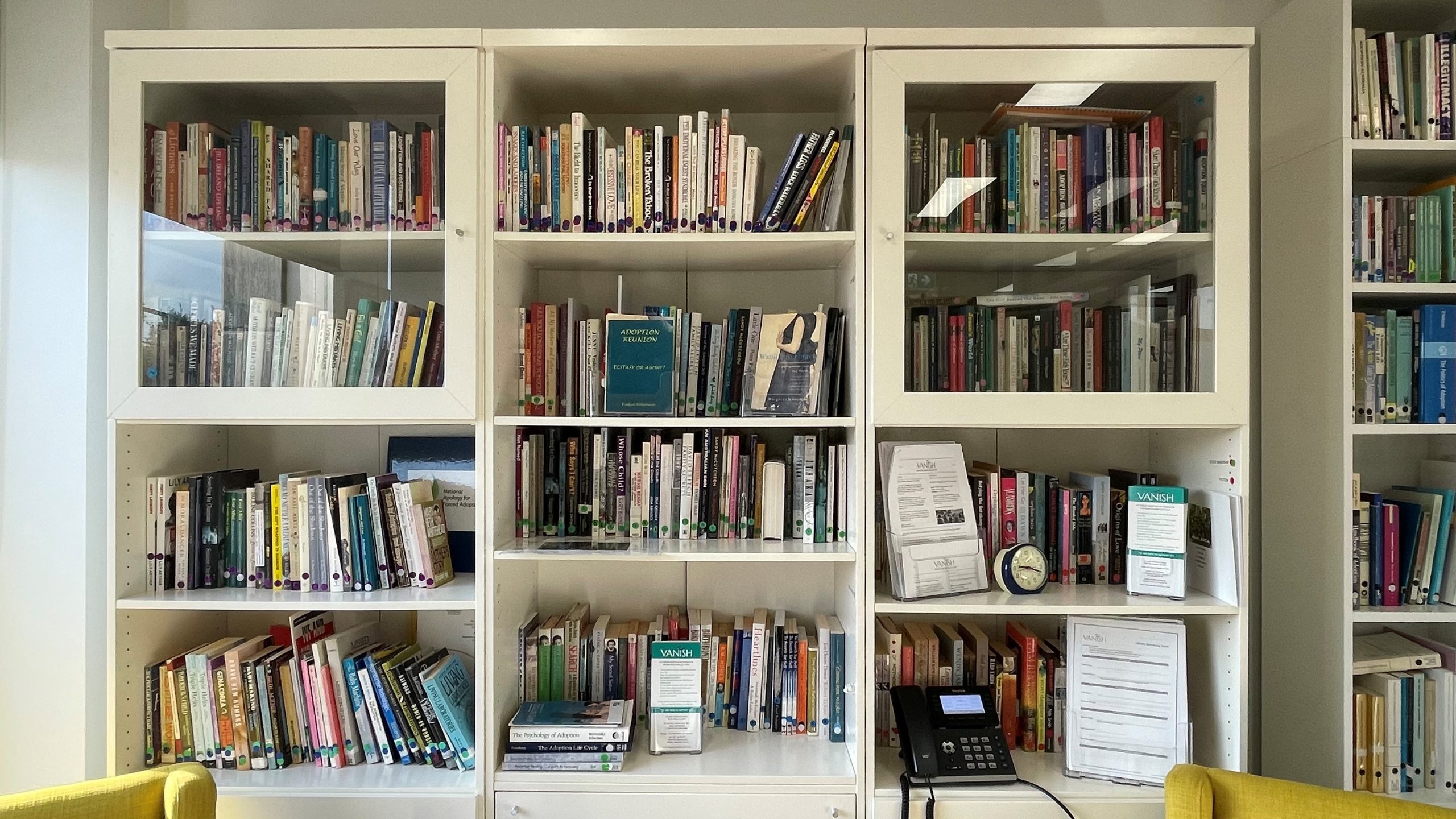

After his dealings with the Catholic Family Welfare Bureau, Brendan turned to VANISH. “VANISH was just fantastic. It was a beacon of light in all of this secret, controlling sense of the church,” he says. “Everyone [at VANISH] was busy and run off their feet, but it was all about, So what do you need? What do you need to ‘close the book’?”

With some encouragement from VANISH, Brendan wrote to his mother directly, but she replied saying that they would never meet in person, rejecting him for a second time. For the next thirty years, Brendan had limited communication with his mother and knew nothing about his father—until, in 2018, a DNA test led him to the truth: he was the son of a celebrated outback missionary priest, Father Vin Shiel.

Brendan points out that the actual search process was long and exhausting, unlike the somewhat compressed version in the book. “I kept wanting to go back to the well, but there were long gaps, you know, like years. And you just eventually hit a wall. You know, a dead end.”

Ultimately, Brendan may never have found both of his parents, nor maintained contact with his mother, without the help of his partner Kate – who Brendan calls “the true hero of the story.”

“There were lots of times when she was just so exhausted by it. And she was running into brick walls and dead ends along the way, and she’d put it down and walk away from it, but because of all the bits she’d found – with my mother, she had sort of found all these electoral roll records and addresses and all this stuff that I thought was totally irrelevant, but it ended up being critical to finding her.”

After finding the identity of his father, who had since passed away, Brendan quit his job and devoted the next five years to researching his father’s life and talking to other children of priests and mothers of the children of priests, as well as lawyers, psychologists, barristers, professors, and social workers. He was driven to both piece together the truth of his ancestry and expose the secrecy and abuse of the church. “I felt as though I couldn’t really rest until I understood, or at least imagined [everything that happened],” Brendan says. “The book was about gathering every conceivable bit of information together and laying it out and trying to understand what happened.”

The result, Tell No One, is a compelling read – eloquently crafted, insightful, and surprisingly humorous at times. During the writing process, his lifelong journalling practice came in handy, both in developing writing skills and providing accurate details of significant events. “Virtually every bit of that book has been in journals, and because you see all the twists and turns, I was able to go back and pull out things that have happened.”

The process of research and writing also enabled Brendan to become closer to both of his natural parents. The more he learned about mothers of the children of priests, he was struck by their common circumstances: often a much younger woman with no financial resources, limited education and career opportunities, and no family support. In other words, someone with no choices. Further, the women were often parishioners who saw priests as the embodiment of God on earth, sworn to secrecy.

Eventually, Brendan discovered that his natural parents were actually living together when he first contacted his mother 30 years ago. He writes openly about the pain of her initial rejections and the lies (including a false name for his father that sent him on a two-year wild goose chase), but with compassion. “I think I say it in the book: You know, I can’t ever love her. But I can forgive her. And I feel enormous sympathy for her,” he says. “And in truth, I probably would have done the same thing, had it been me. So, I get it.”

His father, Father Vin Shiel, is also portrayed with compassion and nuance. Thanks to a progressive archbishop, Brendan obtained his father’s file, containing hundreds of letters written and received by Vin. “I heard his voice,” Brendan says. “You sort of hear between the lines—his attitudes and his inklings and his thinking, and it allowed me the opportunity to sort of create in my mind those chapters that were through Vin’s eyes or viewing Vin.”

Poring over the letters was a cathartic process for Brendan, allowing some insight into the complex man who was a builder, a Bondi Lifesaver, and a trophy-winning ballroom dancer before becoming a priest and touring the world. But Brendan is the only child of a priest that he knows of who has been given his father’s file. “It only infuriates me more to know that I’ve got it,” says Brendan. “And there’s thousands of children and priests around the world that the church still won’t recognize, even though they’ve got a whole bunch of evidence [of paternity]. They’re just at arm’s length. And they have similar information about their fathers.”

This is Brendan’s real mission in publishing this book: to shine a light on the issue of hidden children of priests and expose the hypocrisy of the church. In one study, former priest and researcher Richard Sipe reported that less than half of a sample of 1,500 Catholic priests in the US attempt celibacy. Given that there are 450,000 Catholic priests around the world, it is estimated that they have fathered at least 20,000 children.

Both the children (only some of whom are adopted) and mothers suffer severe psychological consequences, burdened by shame and church silencing. In one survey of 100 children of priests, 56% of participants had either attempted suicide or had suicidal ideation. Of further concern, there is nowhere for these people to go. “This is a really specific, niche group,” says Brendan.

Now Brendan is calling for an independent, secular inquiry from the federal government. He hopes that the book and his decision to go public with his story will help the issue gain traction, but he’s also aware of the difficulty for other victims in coming forward—particularly for believers—and the fickle, fast-paced media cycle. “It might all go away [in the media] …but if there’s a couple of other people that read it, and they’re the mother or they’re the child, and it starts a conversation, and someone hears the truth…they might turn the corner,” he says.

“If it does something good, it does something good. Certainly not going to get rich writing a book,” Brendan laughs. “But I’m glad I’ve told my story.”

—

Brendan’s book Tell No One is published by Allen & Unwin and available from all good retailers.